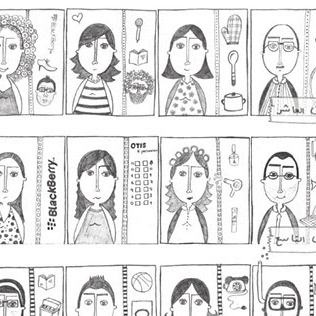

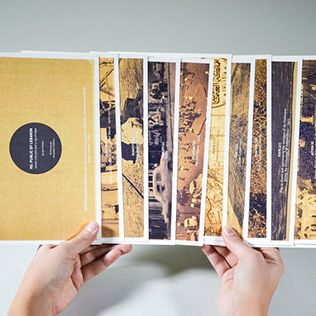

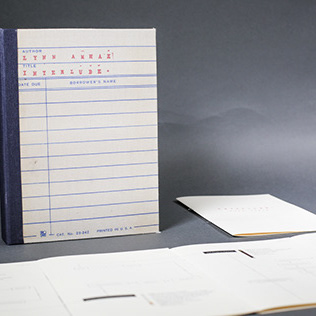

Six years ago, I bought a random stack of old black and white photographs of strangers from a flea market in Beirut. During my thesis investigations, I felt the need to activate them. I called my mother on a Sunday morning and asked her to look for them in the second drawer of my desk in Beirut and mail them to me. Fortunately, a family friend was coming to Boston and was able to bring them along within the next few days. Once in hand, I observed them closely, trying to decipher them. I was fascinated with their appearance — the Arabic, French, English and Armenian inscriptions on the back of some of the photographs and the absurdity of some of the shots. These strangers suddenly became family, but most importantly, I saw a Beirut I never knew, a happiness that was stripped away from the people there in the modern-day era. The photographs date from 1941, the year Lebanon celebrated its independence from the French mandate, up to 1973, a few years before the civil war broke out — the time period when Beirut was called the Paris of the Middle East. I approached the photographs as a set of instructions and had them scanned by a psychic medium. In this capacity, the psychic served as a mediator of the infrathin, observing the photographs and connecting with the spirits of those depicted, be they dead or alive. During the session, she relayed their stories and their messages to me, enabling me to live the city through their eyes.

In the short video, blurred and focused moments serve as a metaphor for the obsolescence of memories and the struggle of the camera’s lens, shutter speed and aperture to capture the memory of these people. As I intervene with the facial recognition language of the camera, both the interface and I attempt to recognize the unrecognizable. Through this process, I grant my audience and myself access to the memories of people we’ve never met and a city we never knew.

In the short video, blurred and focused moments serve as a metaphor for the obsolescence of memories and the struggle of the camera’s lens, shutter speed and aperture to capture the memory of these people. As I intervene with the facial recognition language of the camera, both the interface and I attempt to recognize the unrecognizable. Through this process, I grant my audience and myself access to the memories of people we’ve never met and a city we never knew.